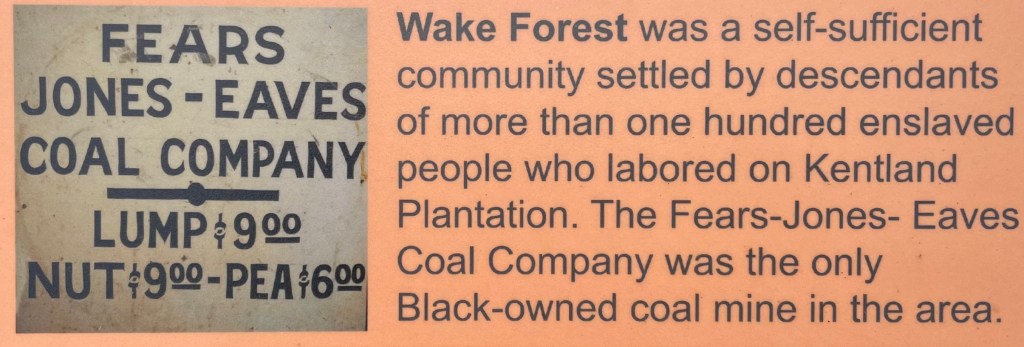

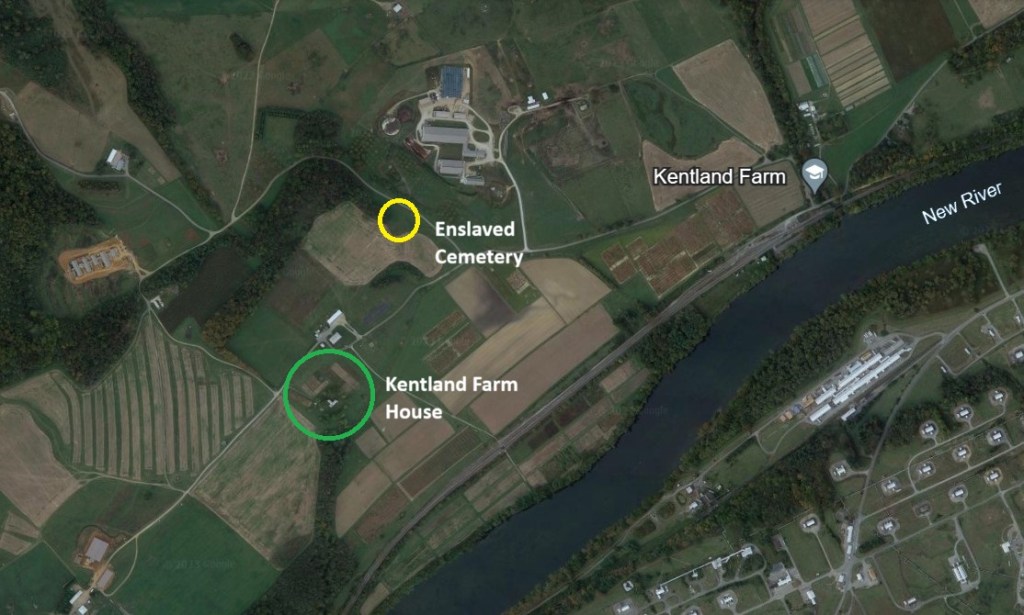

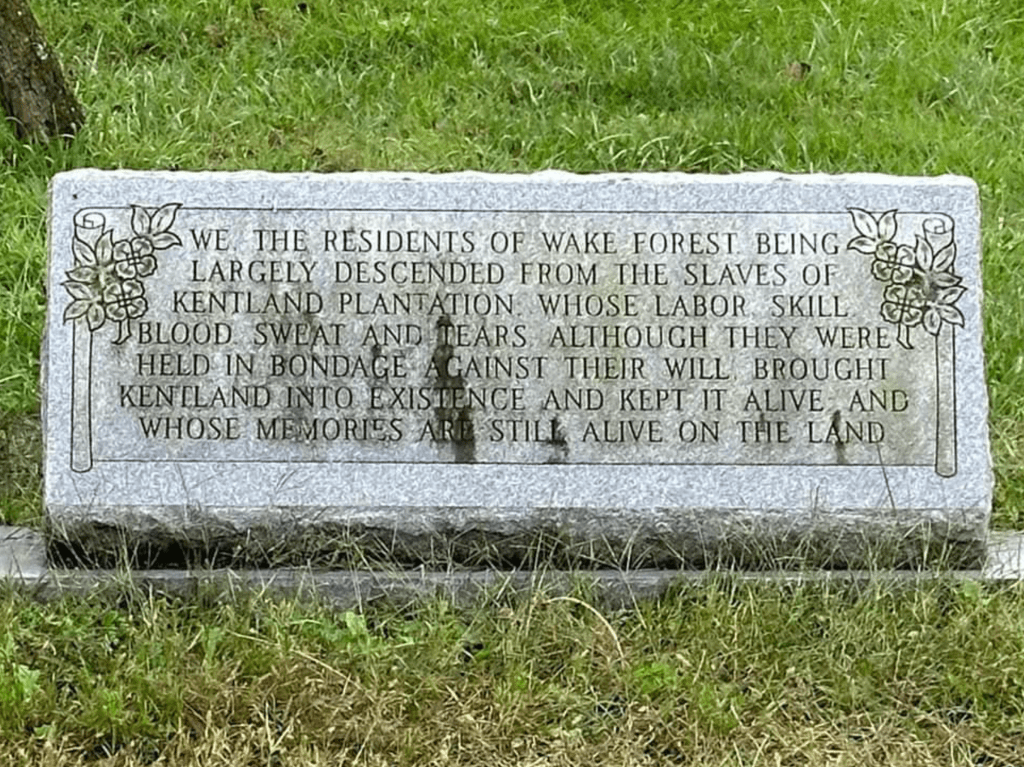

Wake Forest is a historic African American community which is situated at the base of Brush Mountain between Long Shop and McCoy, Virginia. The history of the community is rooted to the enslaved people of James Randle & Mary Cloyd Kent. The history of the ancestors of this community and the Kentland connection has been erased over time. In the early 1980s Wake Forest families with the help of various local researchers begin to gather and report this important history. Since then classes, researchers, interested community members continue discover information and provide reports.

The story of the settlement of Wake Forest at the end of the War of the Rebellion, April 1865, (Civil War) is not clear. According to oral history as reported by Thorp (2017), James Kent gave permission for the newly freedmen to settle in Wake Forest area on his land. According to Johnson (1995) Elizabeth Kent provided the land which became Wake Forest, previously belonged to Phillip Harless but returned to the Kent family. But as told through oral history Cain (2008), Peter Armstrong (born 1837), an African American blacksmith from Tennessee, and Ed Jackson, a freedman, bought the land from Phillip Harless in the 1880’s. He in turn sold parcels to some of emancipated families who formerly toiled on (Buchanan Bottom) Kentland Plantation*. Peter Armstrong was living in Wake Forest in the 1870 census. Researching the deeds would be helpful to shed light on this.

The family names within the Wake Forest settlement remained fairly constant from the 1880 to the 1950 census. The oral histories of residents which were collected over the years (Cain, 2008) mostly agree that the neighborhood was very stable, self reliant, and cooperative in nature.

Based on US Census information, between 1870 and 1920’s, farming or railroad occupations are recorded for most of the men who lived in Wake Forest. That changed in the 1930’s census with the majority of the men working in the mining industry. By the 1950’s census most of the men were employed by the mining industry, either as timberman, digger, loader or carpenter. The local anthracite coal deep mine operations varied in size, from small 20 men truck-mines to very large concerns, employing over 100 men, both African American and white. By the 1960’s the coal from an area adjacent to McCoy was extracted using the surface mine method, but that was the last gasp for that industry.

*Note, Kentland and Whitethorn(e) name was not used until after the Civil War (Johnson, 1995)

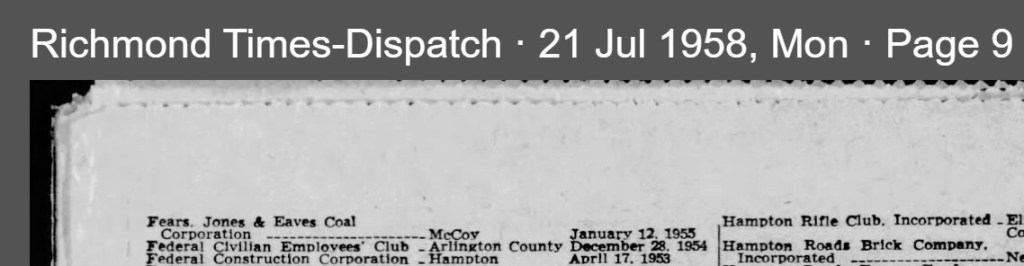

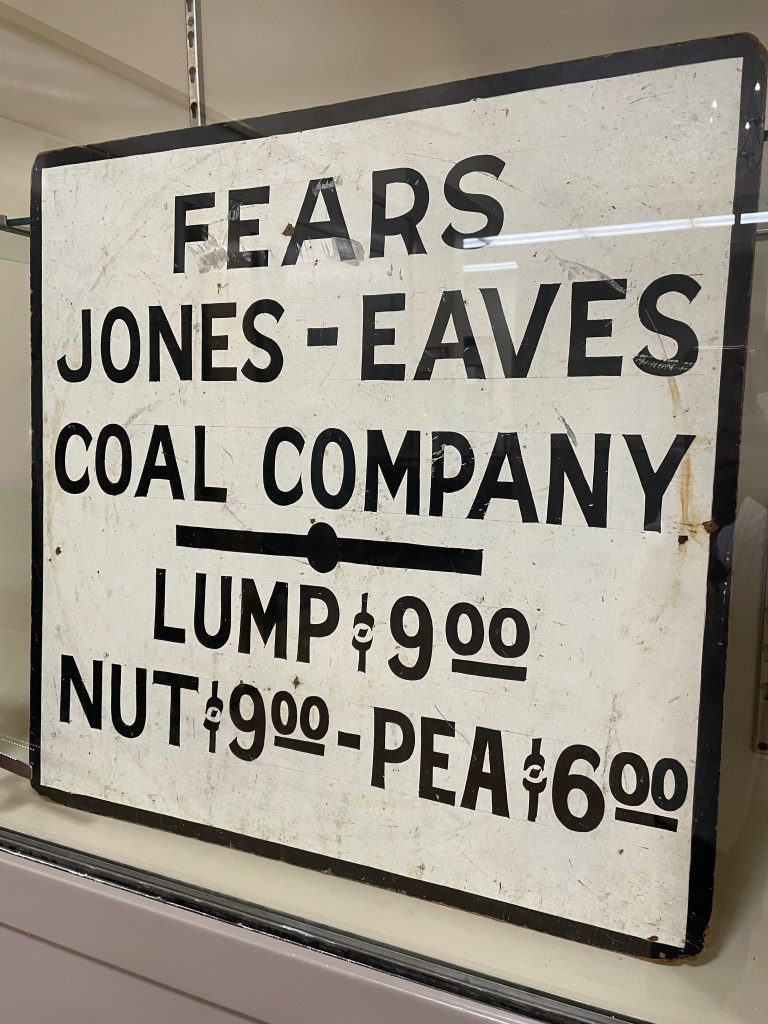

Fears, Jones & Eaves Coal Company

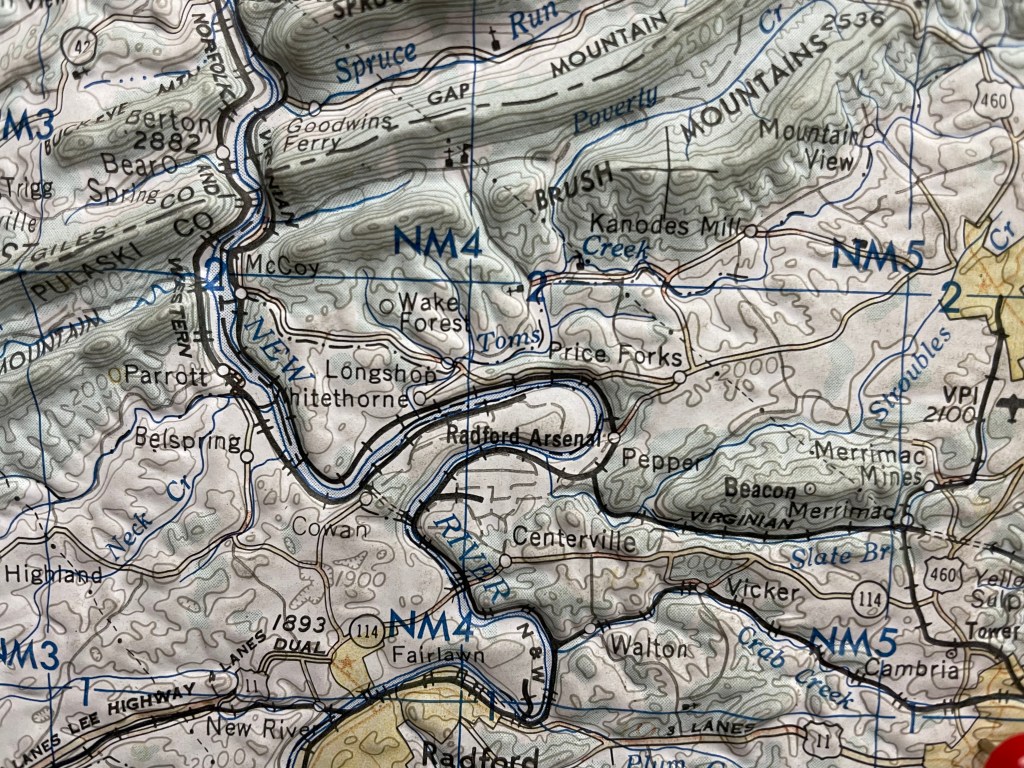

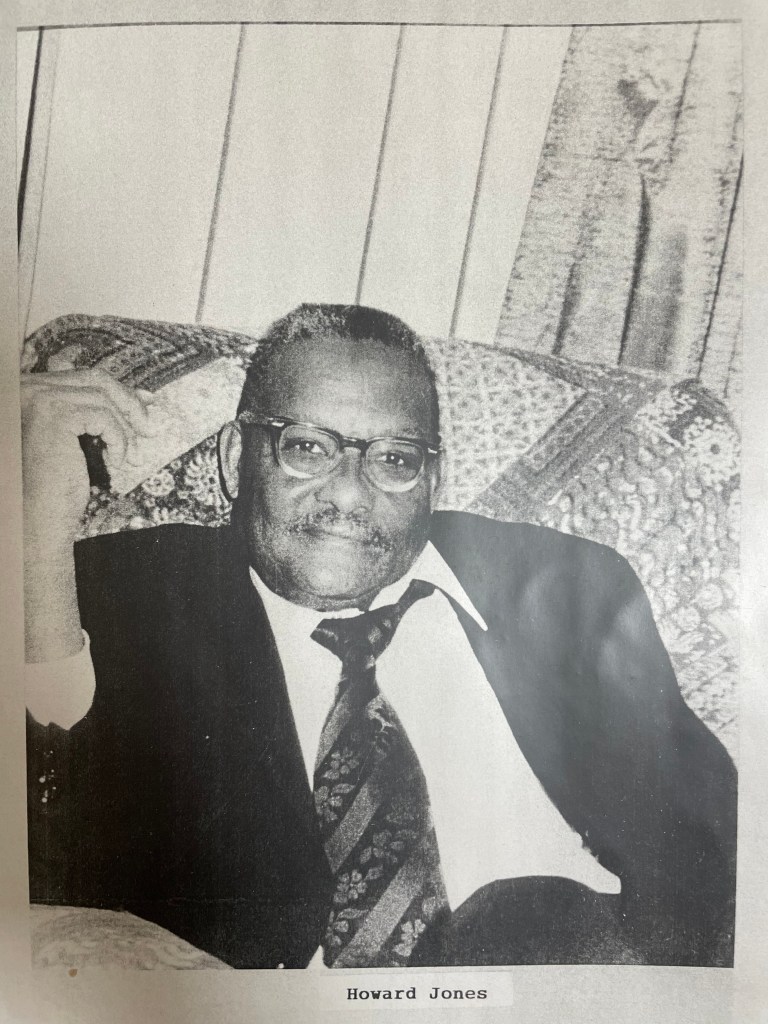

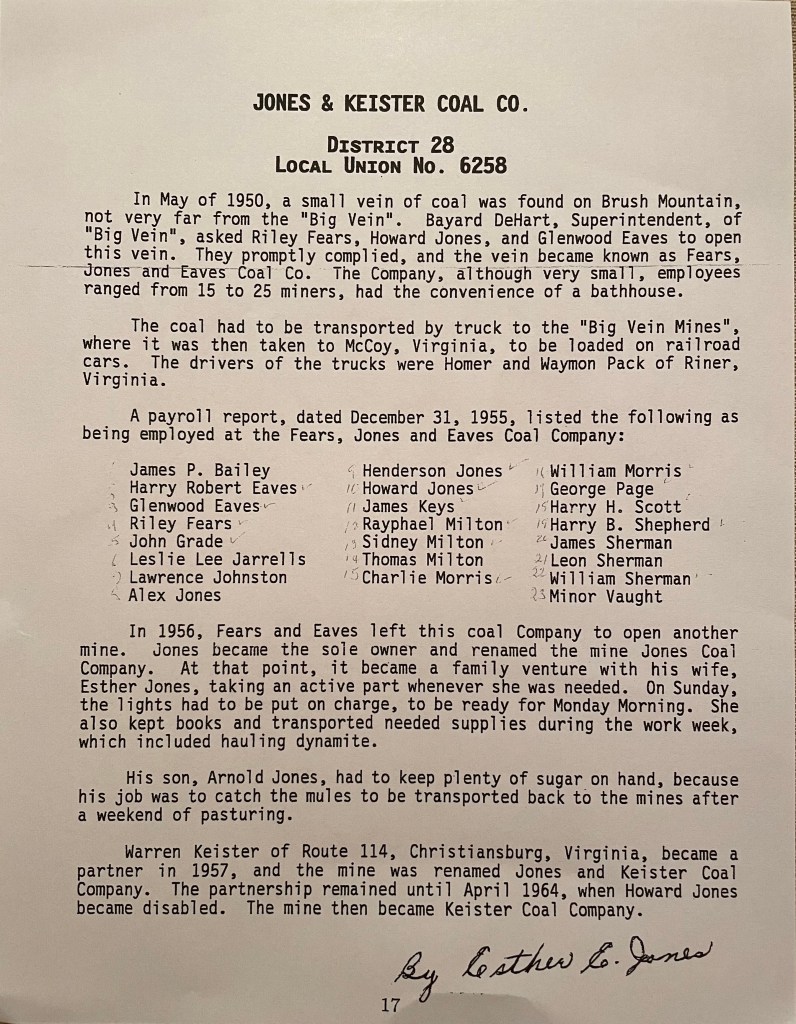

Two African American owned coal operations were located near Wake Forest. We have not learned much about the Sherman operation, but much is known about the the Fears, Jones & Eaves Company. It was started by Riley Fears (1898-1967), Howard H Jones (1915-1983) and Glenwood Eaves (1912-1997), in operation by the early 1950 and registered with the Virginia Corporation Commission by 1958. According to an interview with Esther “Queen” Eaves Jones (LaLone, 1997), Howard H. Jones (husband), Riley Fears (uncle) and Glenwood Eaves (brother) jointly operated the mine but in 1956 her husband ran the operation alone, moving to another seam location (vein). Between 1957 to 1964 he and Warren Keister (white) operated the mine as partners. When Howard H. Jones’ health declined, Warren Keister continued to run the operation. This mine was located up the mountain from Howard and Esther Eaves Jones’ home in the Wake Forest community (map). According to Mrs. Jones, the mine was over 1,800 ft deep, employed a 12-20 men (Black and White) and a couple of mules. Because the mine was not served by rail, the coal had to be trucked down the mountain. In 2008 the office of Abandoned Mines sealed the 7 entrances for safety and stabilized the refuse (gob) piles.

“They used mules at the mines, they pulled the cars, I don’t know what capacity they were doing there, but they worked them in the mines. Every Friday when my husband came home he brought two mules with him . . . put them out to pasture. So that was a chore. Then Sunday evening they would take them back to the mines. They had a barn, stable [in] other words, that they would stay in at the mines, but he would bring them home for the weekend.”

Jones, Esther Eaves. “Oral History with Esther Jones.” By Tyler Bergeron. Virginia Tech Special Collections & University Archives, Ms2019-03. https://digitalsc.lib.vt.edu/ohms-viewer/viewer.php?cachefile=Ms2019-037_EstherJones.xml. November 9th, 2012. Segment 5:50-6:50 min.

Boatmen

In the 1870 US census, Patricia Givens Johnson’s research (1995), and Montgomery County National Register of Historic Places 1989 application, the following African American boatmen moved people and goods on the New River: Jonathan Milton (b 1831), Frank Bannister (before the Civil War he worked the James River), Andrew Boon, John Brooks, James Price, Calvin Bannister, Roland Stuart, George Brown and Lewis Smith.

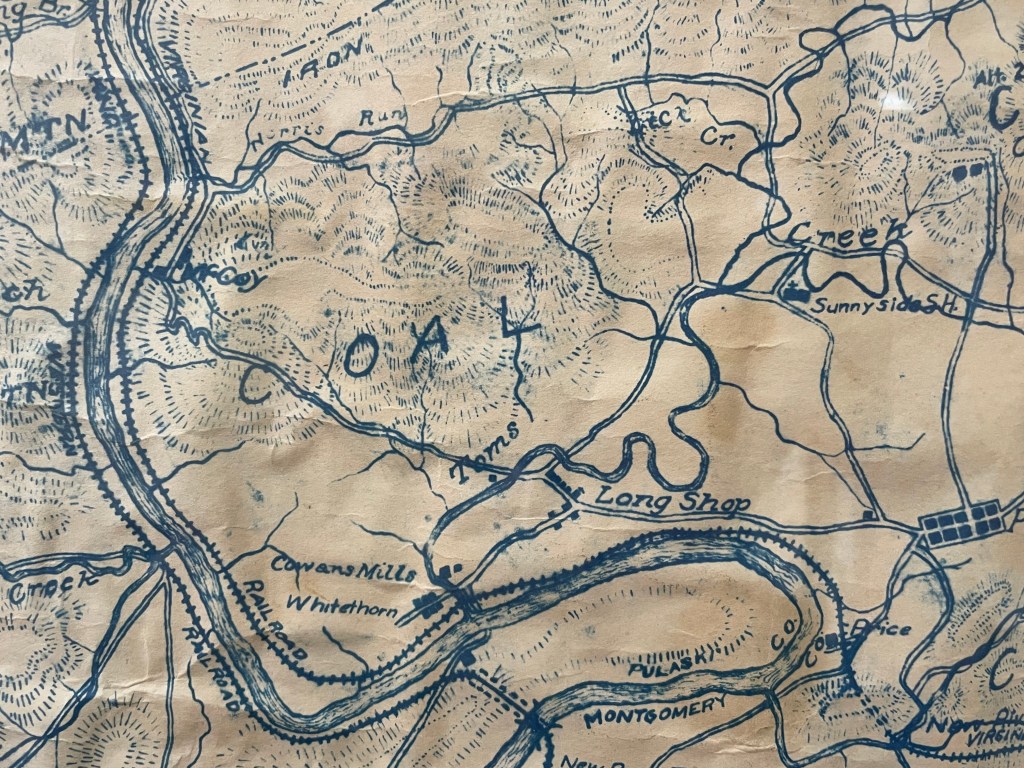

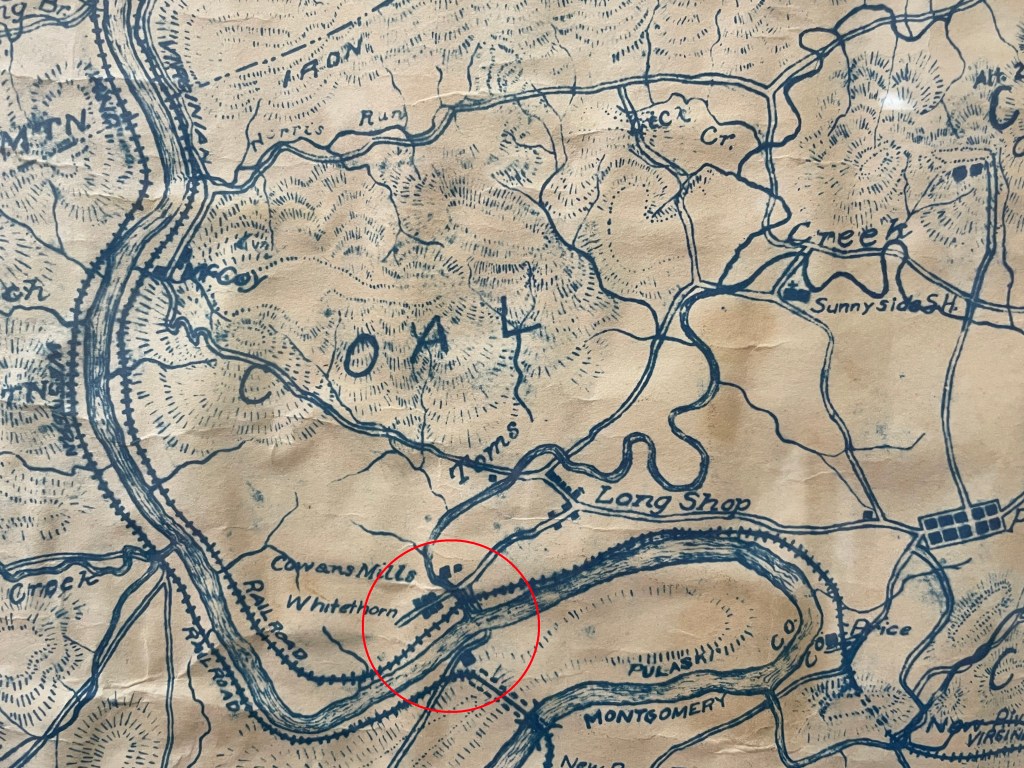

This is the 1925 version of the Montgomery County Map produced by W.F. Wall, Engineer. Note Cowans Mill and Whitethorn on the north side of the New River (red circle). A road is located on both sides of the river. This is the location where the boatmen would transport people, animals, & goods across the river. The the Virginian line train stop was at Whitethorn and Norfolk Western line stop was on the south bank of the river.

Churches and Cemeteries

The document noted below (Cain, 2008) compiles information on the early church’s in Wake Forest through oral histories of community members.

Wake Forest: Voices That Tell of a Faith Community, Cain, 2008. Courtesy of Christiansburg Institute Digital Archive

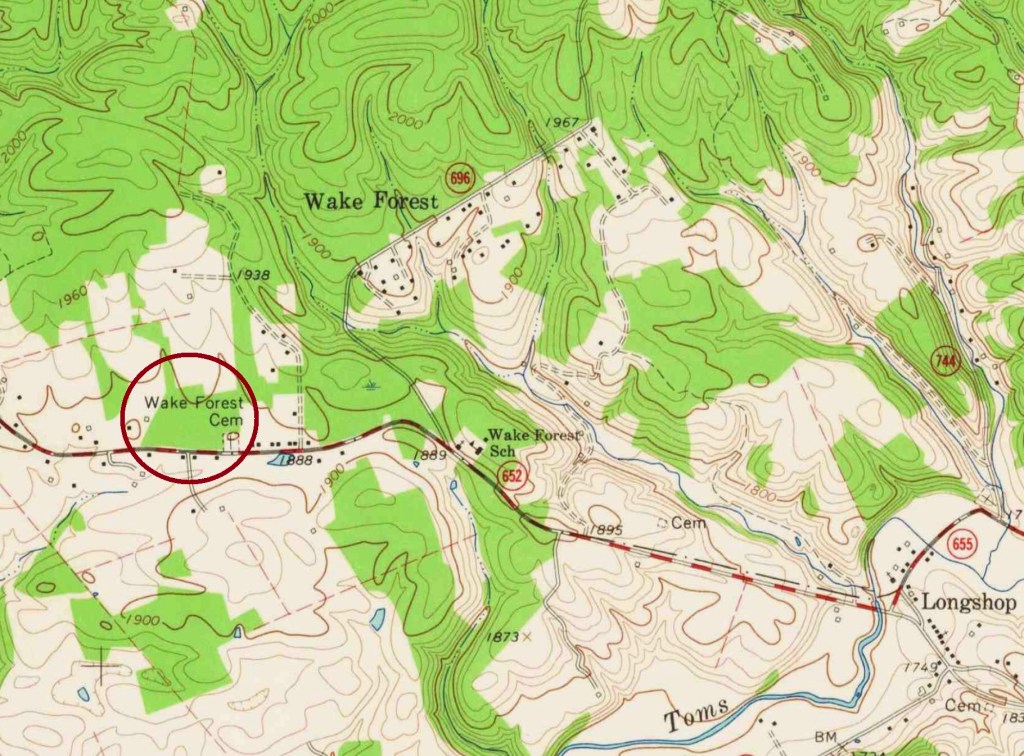

Wake Forest Cemetery is located east of the Wake Forest and Big Vein Roads as circled on the map. Many of the local family members are buried here. The Kentland enslaved people are buried east of the family plot. A modern day marker commemorates this cemetery, no individual markers exist.

Health Care for African Americans in Montgomery County

Midwives were mentioned in Cain (2008). Medical doctors who attended families in Wake Forest included: Dr. Robert E Chumbley in Belspring, Dr. H.B. Huffman from Blacksburg (made house-calls and delivered babies), and Dr DD Phlegar in Christiansburg.

Before 1920’s African Americans needlessly died because the closest hospital was a day’s trip by rail. In the 1916, the vision of a Christiansburg/Cambria hospital became reality by community efforts. It was named “The Christiansburg Colored Hospital.” The new building, located on the campus of the Christiansburg Institute, was dedicated in May 1918 (four months before the ravages of the pandemic) and opened in 1921. It was never fully functional due to a fire in 1922. When the hospital closed in 1925 it was converted into faculty housing. In 1914 the 12 bed Medley Hospital in Roanoke was created, which was not adequate. In response to the 1918 pandemic patient volume, 50 bed Burrell Memorial Hospital in Roanoke was established in 1921. Mrs Ethel “Queen” Eaves Jones reported that her son was treated that hospital in the 1950’s.

Schools

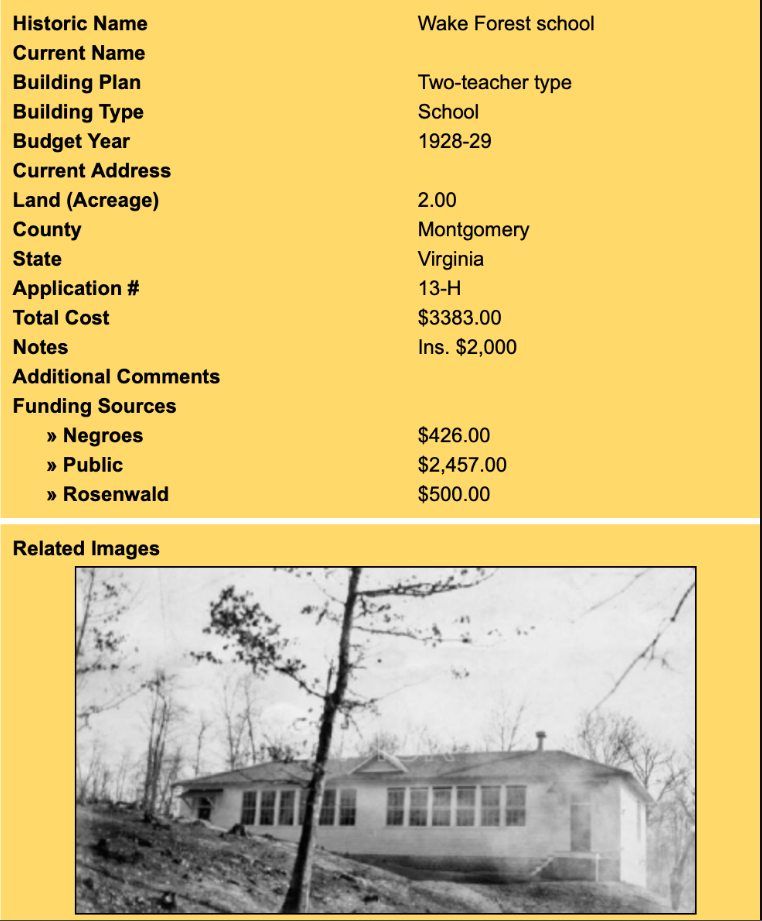

More information needed but briefly, Thorp (2017) noted that in 1869 Elizabeth Kent deeded land that was dedicated for an AME Church and School (in the same building). That log building eventually was used as a Baptist Church. Around 1920 the church burned, and a new Baptist church was built close to the original foundation. It is not clear where students attended school after the church burned. But, around 1928 a Rosenwald funded school was built close to the main road.

Rosenwald Schools are very special and much work is being done to preserve them. Fisk University holds a large collection. If you would like to learn more:

- Preservation Virginia Completes Architectural Survey of Historic African American Rosenwald Schools

- Rosenwald Schools in Virginia: Updates and Preservation Tools Webinar, Virginia Humanities

- Rosenwald Documentary

Books/Documents

- Department of Historic Resources (DHR) documents for the original 1991 application and the 2006 Slave Cemetery and prehistoric Late Woodland archeology documents.

- Walter Hubbard, Virginia Coal: Abridged History, 1990

- Patricia Givens Johnson, Kentland at Whitethorne: Virginia Tech’s Agricultural Farm and Families that Owned It, Blacksburg, VA: Walpa Publishing, 1995

- Linda Killen, These People Lived in a Pleasant Valley, 1996

- Mary B. LaLone, Appalachian Coal Mining Memories: Life in the Coal Fields of Virginia’s New River Valley, 1997

- Morgan Rochelle Cain, Wake Forest: Voices That Tell of a Faith Community. 2008. Courtesy of Christiansburg Institute Digital Archive

- Tonya Mosley, State Working to Close Jones-Keister Mine, Roanoke Times, 2008

- Daniel B. Thorp, Facing Freedom, 2017

Oral History

- Esther Eaves Jones 2000 Oral History, transcription courtesy of Christiansburg Institute Digital Archives.

- Oral History with Esther Jones, November 9th, 2012 (Ms2019-037), Virginia Tech Special Collections, Tyler Bergeron, Interviewer

- Oral History with Charles Johnson, October 18, 2012 (Ms2019-037), Virginia Tech Special Collections, Ryan Noland & Katie Haas, Interviewers

General Resources

- Christiansburg Institute Museum & Archives (CIMA, scroll down to find their extensive archives)

- Freedman’s Bureau 1866-1868, Report of Charles S Schaeffer from the Virginia Counties of Montgomery and Pulaski, with additional information on the Floyd, Giles, Craig, Wythe, and Roanoke

Image Gallery